Following are some of the topics I discussed during a series of Philosopher’s Art Cafes, that I organized. These cafes became part of the Simon Fraser University large number of other cafes in Vancouver and the Lower Mainland.

Talk delivered for a Philosopher’s Art Café on March 15th, 2006, in conjunction with Artists in our Midst Open Studios Walk.

Modernism or postmodernism? (focus on 20th century art history)

If Modernism is associated with the idea of the avant-garde, what happens to the avant-garde in Postmodernism? Has the idea of the avant-garde degenerated into the cult of shock value, seeking the quick impact of advertising? Has innovation become routinized, a mere marketing device? Has the ‘depersonalisation’ of art been balanced by a ‘personality cult’ of the artist-as-self-publicist? Who chooses what is exhibited and why?

Before we even start our discussion let’s try to define, in broad terms what Modernism and Postmodernism are. This is such a vast field, that we cannot hope to do it justice here, there is such an enormous amount of literature and philosophic and critical writings on it, that all we can hope in this forum is just to outline a very general idea.

Modernism started in France, in the late 19th C. as a movement of rebellion by artists against academic traditions and a criticism of existing culture. By experimenting with Dada, Surrealism, later Impressionism and countless other ‘isms’, artists rejected the middle class values and tried to reconstruct society, thinking they could change the world. Of course, as with all other such movements, by the mid 20th c. modernism had become, from ‘avant-garde’, the established norm. At the beginning, the rejection of tradition by artists brought repression in totalitarian regimes, such as Malevitch in Soviet Russia. Ironically, this rebellious trend, fighting against bourgeois values was embraced in capitalist countries and reached its peak in the US, with Abstract Expressionism.

Postmodernism, or PoMo, is considered by some as the next stage, by others as another incarnation of Modernism. When I researched the material for this talk, I was amazed as how diffuse and vague all definitions were, how many different opinions and viewpoints were available. It is really bizarre that we are still talking about some of the current artists as being ‘avant-garde’, when one looks back at the beginning of the 20th c and sees what artists were doing then. I’ll come back to this later.

Postmodernism started in fact with the Dada movement in 1920 and was reinforced mostly by the work of French philosophers such as Leyotard, Derrida and Lacan. It was then embraced by the academia, which has tried (successfully) to present art as an academic and theoretical endeavour, appealing only to the brain, thus emptying art of what it had traditionally done, to communicate not only through ideas, but through emotion as well. Also the end of a personal style, rejection of art history, appropriation, exhibitionism and great use of the shock value. Many see it as an anti-humanist movement, where change becomes the status-quo, leaving the notion of progress obsolete. Depth of meaning is out, newness is in. Mass media appropriation is a common occurence.

I shall not go too deeply into more discussion of definition, this would necessitate a 6 mos. course. Let’s stick with our subject tonight, the State of the Art as we experience it. Most people are not even aware of the philosophical and theoretical debates raging in the art world. They go to see the shows and are either puzzled or dismayed sometime at what they see. Since we are supposed to deal with the visual arts, we should be asking questions based on what we see, although conceptual art, an important component of postmodernism, is about the idea, the concept, and not the form.

Slides:

- Fountain, 1917, Marcel Duchamp.

The French artist Marcel Duchamp. Moved to New York and was the first artist to use the ‘ready-made’ object. After his career as a painter and supporter of cubism, Duchamp fled Europe before WW1 and turned against Cubism with ‘Fountain’. It was an attack on the cultural elitism of early 20th C. With this he blasted away the primacy of the art object, the role of the critic and dealers, the hierarchy of the curators and of the public taste. However, the organizers the Society of Independent Artists of the exhibition rejected the piece, which later disappeared from sight. Later, in the 1950s, with Duchamp’s interest in Surrealism, a dealer asked him to authorize a substitute urinal for an exhibition of his work. He again signed it R.Mutt and substitutes began sprouting like mushrooms. Later he allowed an Italian dealer exclusive rights. Ironic, that this piece which was supposed to deny the preciousness of the art object, became one itself, eventually commanding prices in 6 figures.

‘Fountain’ was voted in 2004 as the most influential piece of art of the 20th C. by 500 British artists, curators and art dealers.

- Felix Gonzales, Fortune Cookies, 1990. This work was offered for a Christie’s auction with a certificate of authenticity signed by the artist. Estimate – $ 6 – 800.000.

Attraction of conceptual art: no skills needed.

- Beuys, Crucifixion, 1962. Conceptual piece

- Warhol, Good Business is the Best Art. He was the natural follower of Duchamp, using the ready-made and the mass media. He understood the value of publicity and of the artist as ‘star’, reaching out to the popular American culture. The borders between High art and advertising have shrunk.

- Marilyn

Increasingly we find writers and critics bemoaning the ‘dumbing down’ of art (at least they did not live long enough to endure the choices of the Turner Prize). Harold Rosenberg, Hilton Kramer. Michael Fried and Karl Ruhrberg held a round table and agreed that “art has become little more than commodity production, investment portfolio and entertainment” They lamented Modern art’s “anything goes” attitude. But in an environment of absolute freedom, what is left for a critic to criticize? The new criticism, especially coming out of Universities, produces jargon-ridden articles which are incomprehensible to anyone without a PhD in art Theory.

- Liam Gillick, Turner Prize 2002, The Wood Way. Text has become the art. Again, it is heavily borrowing from the mass media.

- Rikrit Tiravanija, Social Pudding Factory at the Miami Art Fair.

- Poster for MINI – please define…

- Brian Jungen, Flats

- Tracey Emin, Bed, Turner Prize

- Mike Nelson, Turner Prize, 2002, installation – Trading Station

- Damian Hirst, cigarette butts

- Damian Hirst, Impossibility of Death in the Mind of someone Living, Turner Prize 1992

- Do-Ho Suh, Some/one, S. Korea, New York, 10.000 military dogtags, inside mirrors. Formal elegance and visual beauty, along with conceptual issues of identity, anonymity of war. An example of conceptual art which has retained the aesthetic values.

It is also worth mentioning at this point the enormous costs of conceptual art and its embrace by the very same institutions and market values it is supposed to be rebelling against. The argument that the earlier modern artists were rejected at first does not apply to postmodernism and the high priests of conceptual art. In spite of still calling themselves the ‘avant-garde’ and using such phrases as making ‘cutting-edge’ art, they have now become the establishment, commanding most of the grants and being exhibited in the most prestigious museums.

Too often one has to ask the question “is it art?” and “what is art?”

It was the question which popped in my mind when I entered the large exhibition space at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, in 1980, and thought for a moment that I came to the wrong address. The exhibition consisted of a display of vacuum cleaners and other electrical kitchen utensils, looking more like a show room in a kitchen gadgets store.

The examples are numerous and the question we should dare ask ourselves is, again. In spite of the rampant theories and the pseudo Intellectualization of art, is it not just ‘the Emperor’s New Clothes’ which we are looking at? Is it not time to point out that the glorification of the banal, the bodily fluids, the boredom and poverty of visual stimulation, the superficial ideas presented as deep statements, have proven Hans Christian Andersen’s great wisdom and understanding of human folly.

April 21, 2012

Do artists communicate with the public?

How does the public relate to art in general and to post-modern art in particular? Are some people intimidated by formal gallery spaces? Should art be easily accessible, or do we need to educate the public for a better understanding?

In order to deal with these questions, I’ll give you first a very short overview of art over the centuries and the way it changed. Without these changes we might not have to ask the questions. I’d like to present you with a few questions and hear from you what you think.

How do artist and audience communicate?

How can an artist effectively communicate with the viewer? When is creative work best shoved under one’s bed, and when should one choose to exhibit? What is the purpose of making art available for public viewing? What does the viewer bring to an exhibition context, and how can a safe space be created for artists to be vulnerable and expose their work and for viewers to respond?

“ I don’t know anything about art”, “what does this mean?” “Why is this art?”

We have heard these questions forever and ever. Many people are afraid to express an opinion about art and rely mostly on what they are told. They are afraid that if they express what they really think, they would be considered as boors and lacking basic understanding about art, so they keep quiet and accept the expert opinion of the day. This lack of confidence is common and may lead to the famous syndrome of the Emperor’s New Clothes, but we’ll talk about this later. So – should we talk about art? Should the artist explain his ideas and feelings involved in his or her creation? Does the artist even care about his ideas being understood? Here we come against a common attitude that, I think, borders on arrogance: “Visual art is a visual experience and hence it should not be talked about. “ And what about music? Should all music appreciation classes be cancelled because music should only be heard and not explained?

Let’s see how matters used to be and what role art played as communicator in the past.

In the past artists did not have the same standing as they do today. They were considered as merely craftsmen (a profession dominated by men), who were commissioned to paint mainly religious themes. As almost all people were illiterate and the Bible was read in Latin, the only way the Church could instruct the masses was by illustrating the Bible stories in frescoes, stained glass, windows and paintings.

slide: Stained glass. – the 3 Magi

slide: The story of Adam and Eve by Cranach the elder, 1533, does not need any explanation, the story is clear.

slide: The dissection – Rembrandt

All the works done in the past were figurative, telling a story and thus relying heavily on narrative. There was very little left to the imagination, the main goal being to make the story clear to the viewer. We see this later on, even after the Church ceased being the main patron, as in the Rembrandt painting of the doctors’ guild dissection lesson, or in the Coronation of Napoleon by David, that describes an important political event. Since photography was still in its infancy in the 19th C., it was not used widely, so these historical paintings give us an accurate depiction of the event, the clothing, the architecture and the times. They become essentially documentary works, communicating a clear story. Everyone understands realistic representations of things from real life, no mystery there.

slide: The coronation of Napoleon, David

This is why purely abstract art tends to appeal to a smaller audience. It is common to want to know what you are looking at so you can place a literal meaning on it. But art, even art that is fairly straightforward in its subject matter, has a larger and deeper meaning that goes beyond the literal, and has an emotional component that is very important.

Earlier painters such as the Italian Paolo Ucello had depicted great battle scenes, as, of course, figurative paintings, conveying the movement of the battle. But for the viewer, which one of the battle scenes better communicate the horrors of the war?

Ucello’s decorative, beautiful, almost festive battle scene, painted in mid 15th C. and clearly painted as a commission by a powerful ruler, or Picasso’s Guernica, painted in mid-20th C.?

Towards the end of the 19th c., some artists became dissatisfied with the straight narrative painting and wanted to express feelings and emotion. Beauty was still a very important aspect of art and so we see a new movement in Vienna, the Secessionists, best represented by Gustav Klimt, who died in 1918 and whose lush, decorative paintings are a feast for the eyes. It seems to me that there is no doubt that this painting easily conveys to the viewer feelings of love and tenderness, even though the figures are somewhat abstracted.

slide: Klimt, the Kiss

Then, at the beginning of the 20th c starting around 1915, a most dramatic change occurs in art. With the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, some artists want to express the tremendous liberation and freedom from the old tradition of painting and we see this, now too familiar image by Kazimir Malevitch, painted in 1915. It is a total revolution in the visual arts; but what does it communicate to the viewer?

slide: Malevich

I would very much like to know what you think, since this minimalist approach of black on black, white on white, geometric forms, etc., have been repeated endlessly and are still showing up in exhibitions of what is called now the ‘new painting’. Do these paintings need an explanation in order to be understood? What do they communicate to the viewer? What is the point of repeating the same ideas over and over again? Here is what Malevich himself says about his painting; after hearing this, think if it helped you to understand the work better.

Malevich described his aesthetic theory, known as Suprematism, as “the supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts.” He viewed the Russian Revolution as having paved the way for a new society in which materialism would eventually lead to spiritual freedom. This austere painting counts among the most radical paintings of its day, yet it is not impersonal; the trace of the artist’s hand is visible in the texture of the paint and the subtle variations of white. The imprecise outlines of the asymmetrical square generate a feeling of infinite space rather than definite borders.

At the same time, many artists continued producing art based on the figure, such as Matisse and Picasso, although now the figure is less and less realistic, therefore more difficult to understand.

And then Picasso paints the famous Demoiselles d’Avignon, based on the African masks he had discovered. This is the first step towards another revolutionary visual transformation: Cubism.

slide: Les demoiselles, Picasso, Blue period, Picasso, Dancers, Matisse, cubist, Braque

How did the public react to these works? Have these works mellowed through the years, has the public become accustomed to them, do people understand this art? Like anything new, it takes time to digest the novelty of the new shapes and concepts, but we have to ask the question whether this transformation has led to a smaller number of people who understand and enjoy looking at these works, creating some kind of an elite. On the other hand, have these works enriched and expanded our view of the unlimited possibilities of the artistic imagination?

This was the beginning of an explosion of new styles, different ‘isms’ and the birth of Abstraction.

slides: Motherwell, Clyfford Still, Helen Frankenthaler, Jackson Pollack, Mark Rothko

And then the end of the road: colour field and minimalism, after which there was nowhere else to go.

This was Modernism. As defined by the powerful art critic Clement Greenberg:

Modernism reasserts the two-dimensionality of the picture surface. It forces the viewer to see the painting first as a painted surface, and only later as a picture. This, Greenberg says, is the best way to see any kind of picture. He also believed that painting should have no other meaning than paint on a surface.

So – now we reached the point when our initial question of communication between the artist and the viewer becomes relevant. Now that the figure has disappeared from the painting and the narrative has been eliminated, what are we supposed to think? When one enters the big white box of the exhibition space and is faced with large canvases covered with paint, how does this experience affect us?

Does the power of the colour and the texture of the paint strike one as a strong emotional experience? I know people who said that, when gazing at a Rothko colour field minimalist painting, they broke down and cried. Others, like the group of French tourists I saw once at the MOMA in New York, were laughing and giggling, seeing these paintings as absurd and not at all as art. Could it be that, given the right kind of art education, they would have been able to appreciate these works and gain a better understanding?

Having seen the play ‘Red”, you may now wonder whether the artist even wishes to convey his ideas to the public. We see Rothko disdainfully dismissing the collectors of his paintings as insensitive to the strong feelings he tries to express, while on the other hand he craves the fame and recognition that he cannot get without these same collectors.

Except – for what some still call ‘the dumbing down of culture’: Pop art. It may very well be that after Minimalism literally painted itself into a corner with nowhere else to go, the silliness of POP art, which infuriated Marc Rothko, was the only answer left.

slides: Puppy – Jeff Koons , Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol, who was a superb draughtsman, understood the American psyche and still is one of the most collected artists in America.

Now let’s have a look at landscape painting.

What exactly does it mean for a work of art to communicate with the viewer? Here are a few examples of landscape painting. Which ones are more accessible to the viewer and why?

slides: Robert Genn, Veronica Plewman, Gregg Simpson, Robert Bateman

When we examine the sales records of these artists, we see that the more realistic and easy to understand paintings are doing much better commercially than the more abstracted ones. Does this mean that the more realistic artists communicate their art better than the more abstract ones? Are the artists who simply copy nature easier to understand than the ones who interpret it and give us a new way of seeing it?

Or does it simply mean that we need more education in order to understand the more sophisticated images?

Let’s see now what happens at the post-modern and conceptual art level. Post-Modernism is a rejection of the Modernist values, not a rare occurrence in the art world, when a new vision or style comes into being by rejecting the old one. We saw this happen with the Russian artists who invented abstraction as a demonstration of a new-found freedom, we saw the Impressionists battle against the academic, classical style and now we see the conceit declaring ‘the end of art’, rejecting the visual altogether and claiming that the only thing which counts is the idea, or the concept.

slide: Marcel Duchamps, Fountain

Marcel Duchamps’ ready-made urinal, the famous ‘Fountain’ which I showed you in the last talk I gave, and the idea of the ‘readymades’ was the first big step. It caused a furor when it was first exhibited in the Armory Show in New York, with many arguing that it was not art at all. The discussion it still going on, but now it has also become another ‘contemporary’ trend or fashion. Let’s look at this piece by Joseph Kosuth. How does it communicate at first and how does it change after reading the curator’s statement.

slide: Joseph Kosuth, One and Three Chairs

In this piece, titled “One and Three Chairs” by Joseph Kosuth, we are shown three different ways to picture a chair. We are shown a dictionary definition of the word chair, a real-life chair that someone could actually sit down on, and a photograph of that chair. This artwork is about different ways to show ideas. It presents one chair and three different ways of picturing this same chair. Showing a dictionary definition of the word chair is one way. When I read the definition I imagine a chair in my mind. Showing a photograph is another way to picture a chair. And showing a real-life chair that someone could sit down on is still another way to picture a chair. By showing us three different ways to picture a chair, Kosuth makes the point that there are many ways to show an idea.

All three versions are good ways of showing a chair but they are also very different too. This artwork helps us realize that there are many ways an artist can show his or her idea of a chair. The artist thought this was very interesting. He thought that the way an idea is shown is interesting. In fact, he thought that this IDEA was more interesting that the chair itself. The idea is the most important thing about this artwork, which is why it’s called Conceptual Art.

Let’s have quick look at the winner of the famous Turner Prize competition in 2011 and what the media has to say. But here, again, I have to qualify this by saying that one should also not always rely on the opinion of the media. We have the example of how the media totally panned the Impressionists at the beginning and how mistaken they were.

Read this article by Eleanor Harding:

Creativity: Martin Boyce’s rubbish bin wowed the judges despite its simplicity

Who could mistake this rubbish bin for art? It must be the Turner Prize judges, as winner is announced

By ELEANOR HARDING

UPDATED: 10:11 GMT, 6 December 20

There are no prizes for guessing which competition this piece of, erm, art won yesterday.

This year’s Turner Prize has been awarded to Martin Boyce, whose recreation of a park scene included a wonky bin as its centrepiece.

The bin, which has a slightly rusting frame and an old rag for a bag, was described as ‘pioneering’ and displaying a ‘new sense of poetry’ by judges.

slide: Martin Boyce, the Bin

So – we have finally arrived at what I mentioned at the start: the syndrome of the Emperor’s New Clothes. Is it really art, or is it art only because we are told so?

The bottom line:

Art presents to the viewer a different way of looking at the world, at social issues, emotions, the environment and the landscape around us. The artist brings out that which cannot be seen or felt easily. It is a language that speaks in visual terms, the only was a visual artist can communicate. It is a dialogue, a conversation between the artist and an audience. The same piece of art, viewed by different people, will elicit different interpretations.

If the viewers are intimidated by important museums, art critics and gallery directors, perhaps the wise thing to do is to first keep an open mind and try to look at the arguments of why this is art. And then, after hearing the arguments, to make up one’s mind and not be afraid to express one’s opinion. Some of the works do stand up to what we consider art, but many other do not. Do these artists even care what the public thinks? Do they want to communicate at all? I’d like to hear what you think.

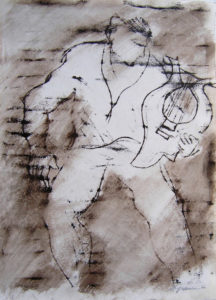

Close Embrace lift-drawing, printing inks From the Orpheus Suite minimum starting bid $250 with increments of $20

Close Embrace lift-drawing, printing inks From the Orpheus Suite minimum starting bid $250 with increments of $20  Orpheus 1 lift-drawing, printing inks From the Orpheus Suite minimum starting bid $250 with increments of $20

Orpheus 1 lift-drawing, printing inks From the Orpheus Suite minimum starting bid $250 with increments of $20  Orpheus 2 lift-drawing, printing inks From the Orpheus Suite minimum starting bid $250 with increments of $20

Orpheus 2 lift-drawing, printing inks From the Orpheus Suite minimum starting bid $250 with increments of $20  Losing Euridice again lift-drawing, printing inks From the Orpheus Suite minimum starting bid $250 with increments of $20

Losing Euridice again lift-drawing, printing inks From the Orpheus Suite minimum starting bid $250 with increments of $20