Garden of Words in The British Columbia Review

The British Columbia Review said the following about Pnina Granirer’s latest book of poetry, Garden of Words:

The British Columbia Review said the following about Pnina Granirer’s latest book of poetry, Garden of Words:

“This well curated combination of paintings, drawings, and poems offers a deeper look into the artist’s life. Much like an imagined visit to her studio, and an intimate conversation over tea, with poppies blooming and forest creatures looming, I am much closer now to the power of Pnina’s prolific oeuvre through reading this beautifully produced volume.”

Follow this link to read the full review.

‘Granirer Paints with Words’

From The Jewish Independent, November 3, 2017.

I am the proud owner of a Pnina Granirer work. More importantly, I am privileged to know the wonderful human being who is Pnina Granirer. After reading Light Within the Shadows: A Painter’s Memoir, I now know more about her art, its influences and styles, and her life, its joys and challenges. I also discovered that she writes as beautifully as she paints, and has a warm sense of humour.

Each chapter features a relevant quote from people throughout history, something they said or, most often, wrote; people as diverse as Roald Dahl, Anne Frank and Shakespeare. In these and her own words, Granirer imparts not only her life story but her philosophies on creativity, education, identity, family, business.

Cynthia Ramsey

Feature Article in the November 2017 Issue of Point Grey Living

0350 Point Grey Living_Nov2017 – Draft3BC Bookworld_Summer2017_pg25

review

Light Within the Shadows: A Painter’s Memoir by Pnina Granirer (Granville Island Publishing, $24.95)

by Joan Givner

ALL ABOUT EVE & PNINA

Living through the Holocaust and escaping Stalinism led to Pnina Granirer’s life of making art.

LIGHT WITHIN THE Shadows: A Painter’s Memoir by Pnina Granirer deftly weaves together two narratives: Granirer’s journey as a Romanian Jew who survives World War II and immigrates to North America, as well as her awakening as an artist who develops into a celebrated painter.

Born in the port city of Braila in 1935, Pnina Granirer grew up under the brutal, fascism of the Iron Guard, an ultra-nationalist, anti- semitic, orthodox Christian movement under the dictatorial direction of Horia Sima. When Ion Antonescu came to power in September, 1940 and soon destroyed the Iron Guard, the Romanian Jewish community were seemingly less endangered than other Eastern European Jews.

But freedoms were steadily eroded. Ownership of telephones and radios was forbidden, cars and finally homes and libraries were plundered. Only much later, when she read I.C. Butnaru’s The Silent Holocaust: Romania and Its Jews, did Granirer understand the full extent of the devastation: half the Jewish population had been slaughtered.

Cattle trucks stood ready to deport the remaining Jews to the death camps, even as the country was “liberated” by the Russian army. This salvation, greeted rapturously at first, turned into another form of persecution. Under Communist rule, Granirer’s father, a committed socialist, was forced into hiding until he could be smuggled out to Israel. The rest of the family eventually followed him, their emigration made possible by Israel’s willingness to pay ransom for Romanian Jews. Granirer and her mother were each ransomed for $100.

She describes her adolescent years in Israel as relatively happy ones, in spite of the poverty and crowded conditions. As an immigrant who didn’t know the language she worked hard to gain an education, met a fellow Romanian who became her husband and, until marriage exempted her, did the required military service. The young couple hoped to remain in Israel but their departure, like that of most “brain drains” world-wide, resulted from the lack of jobs. The Hebrew University had no position for her husband, who had earned his Ph.D. in mathematics there. The U.S, on the other hand, propelled into the space race by the Russian success of Sputnik, was recruiting mathematicians.

Her husband’s career brought them first to the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana, later to Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and finally to Vancouver, where Granirer began to find her way as an artist. As a schoolgirl she had been assigned the dubious and frightening task of producing a portrait of Stalin; in Israel she had found employment in fac- tories that produced painted clocks and lampshades but, lacking a green card in the U.S., she was unable to work. Instead, she discovered a new freedom in drawing and painting to please herself, practising art for art’s sake.

Pnina Granirer in her studio

IT WAS IN VANCOUVER IN 1965 that she made her first association with a gallery—the small Danish Art Gallery run by Peder Bertelsen. There, at the age of thirty, she had her debut exhibition. A year later, a second exhibition was scheduled in Victoria at a small gallery on Pan- dora Street. This brought her into contact with the artists who in 1971 formed The Limners Group—Pat Martin Bates, Herbert Siebner, Karl Spreitz, Myfanwy Pavelic and others. She was honoured that architect and expressionist painter, Maxwell Bates bought one of her woodblock prints.

During a year in Montreal, her camaraderie with artists living bohemian lives devoted exclusively to their art made her question the effect on her work of her own conventional life as a wife and a mother. Her doubts were reinforced by talking to other female artists and by attending a workshop in 1980 with Judy Chicago, whose sensational work The Dinner Party was drawing crowds. Judy Chicago’s statement that no woman artist can ever make it big if she has a family resonated and propelled Granirer into her most ambitious work.

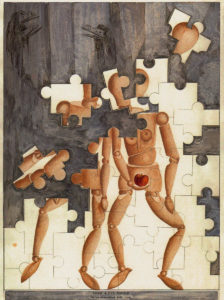

The Trials of Eve (1983) is a series of twelve mixed-media that examine the subjugation of women, beginning with the cre-ation myth in the first two chapters of Genesis. Her model for the figures of Adam and Eve was a wooden marionette—face blank, race undefined, sex ambiguous, limbs easily manipulated. For the voice of Eve she chose the symbol of the Cannibal Bird of First Nations mythology. The structure of the series, to which she added lines of verse, echoed that of a play in three acts.

Adam and Eve Puzzle: to be assembled with Love, from

Pnina Granirer’s series The Trials of Eve.

Her next project, The Carved Stones series (1985- 90), mixed-media works on paper and canvas, was in- spired by the rocks and stones of the Gulf Islands that display wild nature in its purest form, and by her contemplation of the contrast between them and and the man-made statues of historical figures she saw in Paris.

Her involvement with an international organization, Fear of Others: Art Against Racism, inspired Out of the Flames, a triptych depicting war, de- struction and survival. This was accepted by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem for its permanent collection and later included in the exhibition Virtues of Memory: Six Decades of Holocaust Survivors’ Creativity.

ISBN 978-1-926991-83-2

Pnina’s three lives

The Ormsby Review

June 29th, 2017

REVIEW: Light Within the Shadows: A Painter’s Memoir

by Pnina Granirer

Vancouver: Granville Island Publishing, 2017.

$24.95 / 978-1926991-83-2

Reviewed by Janet Mary Nicol

Pnina Granirer was creative from an early age, but she didn’t come in to her own artistically until the “third act” of her life journey. This memoir reveals why this is so as the author recounts her beginnings in Romania, followed by immigration to Israel when she was fifteen and then to North America in1962.

When Granirer eventually settled on Vancouver’s west side with her husband Edmond (“Eddy”) Granirer, a University of British Columbia math professor, she began exhibiting art and building an international reputation while raising two sons.

Granirer has spent most of her life in Canada, yet it is her “back story” — her life in Romania and Israel — which informs these later experiences and consumes two-thirds of Light Within the Shadows.

Using a journal style format, with drawings and photographs accompanying short, thematic chapters, Granirer begins by relaying family histories entwined with accounts of Europe’s shifting political landscape. Born in Braila, Romania in 1935 to Lascar and Carola Solomon, Granirer was an only child. Her Jewish-Romanian parents were a love match, defying their parental plans for an arranged marriage.

In another part of Europe, German leader Adolf Hitler had begun implementing anti-Semitic laws which would lead to the systematic mass-murder of European Jews.

“Houses are secret realms of fantasy and imagination for children,” Granirer writes about the stately two-storey home her family rented in Braila when she was five years old. The house was designed by an Italian architect and owned by a Greek. She grew up alongside other relations, including a female cousin who was like a sister to her. An observant child, Granirer describes secrets within the extended family too. She felt protected and safe, especially trusting of her mother’s strength. Within this atmosphere, Granirer developed a talent for drawing.

After the World War Two broke out, Romania formed an alliance with the Nazis and Granirer remembers her family scrambling into the basement as American bomber planes flew over the city, followed by occupation by Russian soldiers at war’s end.

“A rare oasis in the eye of the hurricane, Braila was a city where most Jews would somehow survive the disasters of war,” she writes. Granirer only learned the full impact of the holocaust on Romanian Jews years later while living in the United States, after reading of I.C. Butnaru’s book, The Silent Holocaust: Romania and its Jews (Greenwood Press, 1992).

Life continued for the author and her family as Romania came under control of Russia’s communist government. Israel was founded in 1948 and a short time later, the opportunistic Romanian regime accepted money from the young country’s government in return for permitting Romanian Jews to emigrate there. Granirer’s father had already escaped to Israel when the author and her mother followed in 1950 under this agreement.

The second phase of Granirer’s life began as she attended high school while living with her parents in a suburb of Haifa. Granirer fulfilled compulsory military duty, married Eddy Granirer, and attended art college in Jerusalem. Her life was carefree and creative. Opportunities in academia for her husband were scarce, however. When the young couple reluctantly moved to the United States, they believed they would return one day.

Eventually settling in Vancouver, Granirer was 39 years old when she was inspired by her young son to create the Childhood Magic series of drawings. “I found my voice as an artist in the early 1970s,” she writes, “after years of wandering through the jungle of artistic styles created by others.” Granirer discovered her finest talent was in drawing and writes that “lines flowed from my pen with a life of their own.”

Her sense of dislocation, the obligations of family life, and the challenges of being a female artist had perhaps slowed her career — but Granirer did arrive. A strong feminist movement had emerged in this period and accounts, in part, for the remarkable success of her series of art pieces entitled “The Trials of Eve.”

Granirer studied the layers of ancient religions and mythologies, including those of the First Nations of the west coast, to illustrate ideas around the biblical story of Eve. The result is a rich visual narrative that has resonated widely and resulted in a book and a film.

More inspiration followed, including a depiction of the mystery and beauty of coastal stones in a series of drawings entitled The Carved Stones, a trio of panels with images based on the Holocaust entitled Out of the Flames, and a series of figure drawings called The Dancers Suite.

Publisher Jo Blackmore (left) with Pnina Granirer and publicist David Litvak at Artists in our Midst. Photo by Doug Williams

Granirer is co-founder of Artists in Our Midst, an annual event, now in its twentieth year, on Vancouver’s west side. Artists open their homes and studios to the community over a weekend in June.

Although Granirer has achieved much since leaving Europe as a teenager, she provides a satisfactory conclusion to her memoir by recounting her 2015 visit to Romania. She succeeded in viewing her childhood home in Braila and found people who remembered her and her family. Returning to Vancouver, she reflects on her mortality and life’s mysteries.

Granirer’s writing — and art work — has undoubtedly helped her in this rumination. Readers are rewarded too, with an enlightening and insightful story of an artist’s life.

Janet Mary Nicol is a secondary school history teacher in Vancouver and a freelance writer. She has written local histories about Vancouver and its people for BC History, Canada’s History, and Labour/Le Travail. She also volunteers with the BC Labour Heritage Centre. Her writing blog is at http://janetnicol.wordpress.com/

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

Pnina Granirer: Imagination Games,

by Gregg Simpson

The fact that a senior artist, mainly known for paintings, prints and mixed media works can turn out such an up to the minute exhibition of digital photographic works was a revelation to me. Pnina Granirer’s Imagination Games shows us that the so-called Vancouver School of Photo-Based Art has a rival in an artist trained in the old world art academies in the mid-20th century who has resisted their arid, theory-laden approach to create these works which are every bit as contemporary.

This difference in approach reminds me of the statement by French art historian, José Pierre, writing in his 1979 book, Surréalisme: “Today it is a fact that the art market has placed itself almost to a man under the flag of a dominant ideology… American Minimal Art, and its paler European imitations, only accord favour to painting which is only painting, that is to say that which forbids any modulation, vibration, emotion, form, any manifestation of the sensitive and even more of the unconscious and of myth. This admirable conjugation of puritan iconoclasm, of neo-positivist empiricism and of Wall Street is sometimes – like the olive in a dry martini- accompanied by a pinch of Maoist ideology.” Granirer never bought into that school and stayed true to her roots.

But now she has turned out to have her own, equally contemporary approach to photographic art. By using photo editing software, Granirer alters and recombines street scenes that she photographed in Mexico a few years back. She realigns the streets, invents new perspectives and creates new colours for the poignant village streets she photographed. They make a spell binding installation.

What struck me as a strong point is also a source of some irony. Knowing of Granirer’s less than favourable opinion of American minimalism and conceptual art, movements she has had nothing to do with while blazing her own trails in the west coast rainforest, it is worth noting the strong compositional element in this series. The repetitive elements in the imagery she has digitally collaged into existence remind me in a way of geometric minimalist painting or sculpture. The strong vertical edges of the old buildings give the pieces a bold framework that supports the lyrical atmosphere and the poetic transformations she has created.

What is different from a lot of minimalist or conceptual photography is the sense of the poetic. Granirer’s geometry shows us the “manifestation of the sensitive” Pierre spoke of, in a new series that puts the lie to assumptions about photo based art in Vancouver’s fractious artistic scene.

At the Sidney And Gertrude Zack Gallery, 950 W. 41st, Vancouver, until March 4, 2012

THE WHISPER OF STONES at the Two Rivers Gallery, Prince George BC, Oct. 12, 2012 – Jan. 6, 2013

Catalogue essay by George Harris

Pnina Granirer was born on the cusp of World War II to a Jewish family in Romania. Though her family may have fared better than very many, the upheaval into which she was born continued well into the first few decades of her life, significantly influencing her development as an artist. Later on, as an established artist, themes of stability dominated her artwork. Timeless and enduring stone formations, geological features and iconic symbols of human material culture captured her attention and figured prominently. The Whisper of Stones samples a cross-section of this work from later in the artist’s practice, bridging the eighties to present day.

Granirer moved numerous times in her first thirty years, from Romania to Israel, to USA and eventually to Canada. A turbulent and eventful period for the artist, she endured Nazism and communism, adapted to numerous changes in language, completed a period of military service, married and had her first child and heeded her lifelong artist-calling by attending art school. These and other important details of the artist’s life and practice are adroitly described in Ted Lindberg’s Pnina Granirer: A Portrait of an Artist (1998).

Lindberg charts the artist’s course into the late 1990s but of most relevance to this discussion is the lead-up to the carved Stones Series starting in 1985. Granirer’s work developed dynamically into the eighties borrowing from traditions of expressionism, figuration, stylisation and the decorative in art. Granirer reflected important aspects of her own life in her work including meditations on family, even using her children’s footprints as compositional elements. An important body of work, called The Trials of Eve, examined a range of feminist issues and landscape assumed a more prominent role. Throughout this time Granirer actively exhibited internationally. Culturally, particular referents were frequently introduced into her work including Hebrew text, a recurring image of a specific charm, or images of Kwakwaka’wakw dancers. Granirer was a well-established and highly regarded artist by the time she started work on the Carved Stones series in 1985.

The inspiration for The Carved Stones Series took Granirer by surprise during a visit to Roberts Creek on the Sunshine Coast:

“It was late afternoon. Low sun brilliantly reflected in the small waves moving back and forth in the gentle breeze. The tide was just starting to come in, accompanied by the piercing cries of the seagulls. I climbed upon a huge black boulder and sat on its warm, dark surface. All of a sudden, out of nowhere, a powerful feeling swept over me and my heart raced at the sound of the waves. I understood that this rock upon which I was sitting had been there for time immemorial; it was older than history and had perhaps witnessed events that we will never know. It held mysteries in its silent, stony bosom, stories never to be revealed. I had the extraordinary feeling of a curtain being lifted, allowing me to see the universe unfolding.” (Lindberg 1998)

Blue Rock, Opus #2 (1985) is one of the first images to emerge as part of this new series. Two rocks, one larger than the other, and a series of mussels are rendered in paint while their shadows are drawn in graphite against a white unembellished backdrop. These forms stand alone, immovable and monumental. Adorned with barnacles, there is a timeless character to these forms that possess an enduring and authoritative presence.

Just as stone reflects the impact of natural forces, it is an important element in uncovering aspects of human history as well. The enduring quality of stone ensures that some of the oldest reflections of human civilization remain. Granirer sees these works, like Nike of Samothrace (190 BCE), or the Venus of Willendorf (25,000 – 28,000 BCE), as embodiments of human history. She remembers a significant moment when, shortly after starting on this body of work, she found herself in Paris. Taking note of the stone sculpture she encountered in France, she began to reflect on and compare them to the remarkable rock formations she had encountered closer to home.

Carved Stones, mixed media on paper, 40×60 in.

The artist saw these man-made monuments as symbols of our separation from nature and as symbols of power, many of which were reflections of religious beliefs that promised deliverance to paradise at the end of life. How arrogant, she thought. We have organized ourselves into groups, towns and civilizations seeking to emerge from nature. We have sought to harness and exploit it, losing track of the fact that it was to bolster our chances of surviving in the face of nature that we organized ourselves in the first place. In these monuments it is often ourselves that we reflect and not that which has the power to release earthquakes, tidal waves and manifold calamity in the face of which we are powerless.

She draws these natural and manmade elements together in Time Bridge with Nike (1988). Nike dominates the composition’s centre, while to its left and right she has overlain renditions of the Galleries. The sheets of paper onto which the Galleries have been rendered are each torn along their inside edge, giving shape to her theories of a rift between civilization and nature. As Lindberg points out, stone is the common denominator between the two; both man and nature have shaped it[1]. And in Time Bridge, Granirer seems to bring them together as if to instigate some form of symbolic reconciliation.

Time Bridge with Nikke, mixed media on paper, 40×50 in.

Granirer described her justification for bringing these elements together in an artist’s statement from 1989 for The Carved Stones Series, an exhibition at the Art Gallery of the South Okanagan:

“Historically, Canada’s cultural past is very short. My work brings Canada, through its majestic legacy of nature, into the universal cultural context, by juxtaposing stones that chart the history of the earth to stones that chart our civilization. By placing stones carved by man into a landscape of stones carved by nature, this imagery creates integration as opposed to principles of conquest and domination. These mixed-media works on paper focus on intimate close-ups of stones whose organic, bone-like forms raise questions about our roots in a far removed past. These are soft, rounded, feminine shapes, but the power they convey is masculine. This integration exudes a feeling of wholeness and peace. Culture returns to nature and pays homage to its roots.”

Such a return to nature appears to be the impetus behind Visions of Nike. In this mixed media work, sloping formations towards the top right of the image appear to flank a band of material resembling a dried-up river that extends beyond the image plane. Circles punctuate its surface suggesting something reflective and lighter in colour underneath. Adding to this surreal tableau, iterations of the familiar sculpture seem to hover over the circles as if poised to descend in a kind of healing gesture to fill the voids.

This third rock formation, a rock bed with circular cavities, had a significant impact upon the artist and appeared in numerous artworks between 1986 and 1991. Granirer described the moment she first encountered it:

“In front of me, a strange sight of deep, round holes carved directly into the bedrock. They are filled with rainwater and thin, sharp blades of wild grasses grow from their depths, like fine drawings reflected back into the liquid mirror. What is this place, this moonscape invaded by rich life forms, and what are these unusual shapes? Has a giant, carrying a huge cookie cutter, been hollowing out these forms for a banquet of sweet giant food? Is this a real place or only a vision?”

Granirer had discovered an old disused quarry where millstones had been cut for use in the pulp and paper industry from around 1932 to 1936.

Mystery at Gabriola, mixed media on paper, 22×30 in.

Discovery at Gabriola 5, 6 and 7, were first exhibited together in Strasbourg in 1987. Poet Jean Christian described this exhibition called Les Rochers Bleus at Galerie Aktuaryus:

“The show consists of watercolours and drawings, but also more complex works into which Pnina Granirer introduces new elements, giving them magical powers. All of the first room at the Aktuaryus Gallery, 23, rue de la Nuée-Bleue in Strasbourg, is as if illuminated and transfigured by them. This exhibition as a whole emanates an almost magical clarity, quite unusual these days.

The artist, of Romanian origin, but settled in Canada for over 20 years, went searching for this magic on the shores of the Pacific near Vancouver, where, by a quirk of fate, she was initiated into a new world.

Of course, anyone could discover rocky islands and strange figures carved by the winds and the tides over thousands of years. But Pnina Granirer has penetrated much deeper into the landscape, discovering an abandoned millstone quarry cut out of the living rock, today a strange site one might attribute to a long lost civilization.

Wild grasses have grown in the geometrical cavities, water has filled them and the day is reflected in them like in some deep mirrors. Pnina Granirer has put her very own personal stamp on the exhibition, by creating a marvelous series out of these secret places, entitled “Discovery at Gabriola”.

Even though the artist has already exhibited twice before in Strasbourg and thus is no stranger to us, she still surprised us by this new height that more than justifies the international reputation she has developed for quite a few years now. All the more so, since far from repeating herself, she treats the most original themes with great control and sobriety, suggesting the silence of the space disturbed by the rumbling of the ocean and the piercing cries of the seagulls. And also by an overwhelming poetry.”

In 2005, the Fundación-museo Granell in Santiago de Compostela in Spain hosted an exhibition called Surrealismo Costa Oeste: una perspectiva desde Canadá (West Coast Surreal: A Canadian Perspective) which included along with work by Gregg Simpson, Gordon Payne and Martin Guderna, Granirer’s work on the basis of its “poetic vision and lyrical abstraction”. This exhibition was followed by others in Coimbra, Portugal, and Santiago, Chile that included related selections from the Carved Stones Series.

Some years later, after revisiting work from the Carved Stones series, Granirer experimented with responding to a landscape by superimposing figures drawn on Plexiglas that the artist distressed and then painted. These new figures followed the form of the landscape she had rendered two decades earlier, stretching and conforming into poses that bring dance to mind. Granirer named this series Humans in the Landscape (2010). Figures respond to the foundation over which they are laid, representing a kind of improvisation that is both individual and familiar to us as we each negotiate the world in our own unique way.

Granirer’s eventful life is reflected in the artwork she has produced. It holds the imprint of her childhood memories and captures her family, her discoveries and those aspects of her life that held her in thrall. Though her work is biographical in its many personal details, it is also familiar in its capacity to mirror aspects of a shared human history and the character of the human condition. Rich and varied as it is, in her later career, Granirer chose to revisit a body of work that was significant and influential at the time of its conception and in which, years later, she found new meaning.two rivers gallery,

The Whisper of Stones bridges a period of nearly four decades. During this time an important and recurring motive has been the remarkable stone formations that Granirer encountered on BC’s coast. Permanent and enduring, time is neither measured by years nor generations for these formations, but by the rise and fall of civilizations and the passage of millennia. It is humbling to consider ourselves in this context. Both by the measure of the lives we spend here, and by those things we leave behind, our time on this planet is fleeting as a whisper echoing off stone.

The Whisper of Stones

Two Rivers Gallery, Prince George, BC, October 11, 2012 to January 6, 2013

In the mid 1980s, Pnina Granirer, a well established artist living and working inVancouver, started to produce a body of work focused on rock formations around the southern coast of BC. For Granirer, whose work around that time reflected her interest in various aspects of human history and landscape, this represented somewhat of a departure.

As Ted Lindberg in his book, Pnina Granirer: Portrait of an Artist, observes: “These paintings were treated with the intimacy normally lavished on still lifes.” Images like Blue Rock Opus #3, the Blue Stone series and the Stone Head series, clearly reveal that to which he was referring. The features she paints are detailed and often disassociated from the context of the land around them as if some type of portrait. As her fascination with rock formations continued, she found herself on Gabriola Island where she was shown an old sandstone rock quarry that had been used in the first half of the twentieth century as a source for millstones for the lumber industry.

Delighted by the surreal and otherworldly discovery, her interest in it endured until the 90s and resulted in a series of related works. Included here are paintings like Visions of Nike and the Carved Stones, which juxtapose iconic, man-made sculptures with the remarkable rock formations she had documented. Representing culture on one hand, and nature on the other, Granirer painted them together symbolically reconciling culture with the stone landscape, the likes from which they were once hewn.

Granirer’s work continued to change and evolve and by the late nineties, she turned her attention to the figurative. In collaboration with dancers and dance companies in BC and Yukon, she developed new bodies of work that examined the human form. Recently rediscovering her work from the 19880s, Granirer has started to unite the two interests. Using original images of rock formations as background, Granirer superimposes new human forms rendered on Plexiglas. The fluid figures appear to stand in for the now absent images of sculpture she originally juxtaposed. On another level, the become metaphors for the brief presence of our species on this planet when measured against geological time and reminders of our own mortality.

George Harris, curator

To visit the exhibition click on these links:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JxAeRffRCC0

and

http://www.scribd.com/doc/114509623/Pnina-Granirer-The-Whisper-of-Stones

News: October 2008

The Glenbow Museum in Calgary has just acquired Pnina Granirer’s major work, THE TRIALS OF EVE, for its permanent collection.

Glenbow curator Monique Westra describes the work as “daring, moving, witty, original and intelligent”. THE TRIALS, completed in 1981, consists of 12 mixed media drawings and 12 poems. It is structured as a narrative, a play in three acts, and follows the fate of women through the ages. The TRIALS is based on the ancient myth of Adam and Eve and incorporates references from art, religion and history, substituting the Cannibal Birds for the ubiquitous snake. It ends on a positive note, hoping for men and women to resolve the puzzle of which they are a part.

The work has been published as a prize winning limited edition book, a softcover book and a film. It has been exhibited several times and discussed during panel discussions and lectures.

News: June 2008

Pnina Granirer (Vancouver) is one of three Jewish artists who responded to a questionnaire circulated by the authors of Feminist Theology with a Canadian Accent : Canadian Perspectives on Contextual Feminist Theology. Her Trials of Eve suite (1993) is a series of twelve mixed-media paintings, each accompanied by a poem. Each painting portrays an “act” or episode in the drama of creation, “fall” and redemption, from the “testing” of Eve in the garden to the hoped for reconciliation between the two severed halves of humanity, female and male. The title of the work evokes both a court trial and the trials of Job; art critic Lucy Lippard observes that “The Trials of Eve, unlike those of Job, are to be conquered in the name of compassion and understanding.” The two main paintings examined here are scenes in Act Two of the drama, from The Fall to The Labelling of Eve by Unanimous Consent as the one whom Jews, Christians and Muslims alike “put … in a golden shrine as long as she is good and reads her script as written: the Mother and the Whore. It is all God’s will!”

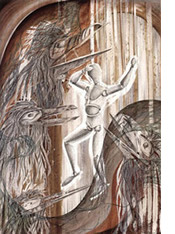

The Verdict portrays Eve being found guilty for all time, particularly by Christian theologians with their doctrine of the Fall and the woman’s culpability in it. In her commentary on the painting, the artist notes that “In 418 A.D., a Church synod declared that death was not a necessity of nature, but rather a direct result of Eve’s disobedience.” Granirer’s Eve (and her Adam) are portrayed as marionettes, indicating that both are stock figures for humanity—“race unimportant, … sex unclear, easily manipulated.” In this retelling of the myth, there is no serpent; the primal woman is tested by Cannibal Birds. In west-coast Aboriginal mythology, the Cannibal Bird attempts to devour a young man in quest of his song, believed to express a person’s inner being. In the intense struggle to prevail, the initiate becomes a wild creature, and discovers his song when he returns to his people and regains his humanity. For Granirer, Eve’s eating of the fruit is “a deliberate and independent act, the first act of free will.” The artist found the Cannibal Bird symbolism especially suitable to express Eve’s inner process of seeking independence from the dictates of a God who “sets the trap for his own creation.” In The Verdict, Granirer explains, “the Cannibal Birds have become part of Eve’s life, haunting her from within and without. Symbols of the guilt placed on women, they have infiltrated her very soul.” The accompanying poem expresses the verdict verbally: “We, of the Highest Court / of Men made in God’s image, / hereby decree / that Eve shall be / forever haunted by her sin. / This is our verdict: / she is guilty for eternity.”

The Verdict portrays Eve being found guilty for all time, particularly by Christian theologians with their doctrine of the Fall and the woman’s culpability in it. In her commentary on the painting, the artist notes that “In 418 A.D., a Church synod declared that death was not a necessity of nature, but rather a direct result of Eve’s disobedience.” Granirer’s Eve (and her Adam) are portrayed as marionettes, indicating that both are stock figures for humanity—“race unimportant, … sex unclear, easily manipulated.” In this retelling of the myth, there is no serpent; the primal woman is tested by Cannibal Birds. In west-coast Aboriginal mythology, the Cannibal Bird attempts to devour a young man in quest of his song, believed to express a person’s inner being. In the intense struggle to prevail, the initiate becomes a wild creature, and discovers his song when he returns to his people and regains his humanity. For Granirer, Eve’s eating of the fruit is “a deliberate and independent act, the first act of free will.” The artist found the Cannibal Bird symbolism especially suitable to express Eve’s inner process of seeking independence from the dictates of a God who “sets the trap for his own creation.” In The Verdict, Granirer explains, “the Cannibal Birds have become part of Eve’s life, haunting her from within and without. Symbols of the guilt placed on women, they have infiltrated her very soul.” The accompanying poem expresses the verdict verbally: “We, of the Highest Court / of Men made in God’s image, / hereby decree / that Eve shall be / forever haunted by her sin. / This is our verdict: / she is guilty for eternity.”

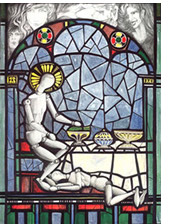

The next scene, The Sentence, is an unusual one to find in a series about Eve, especially by a Jewish artist. Granirer relates that on a visit to Strasbourg Cathedral in France, she was “shocked to see that the craftsman who had designed the window chose to portray Mary Magdalene [sic] lying flat on her belly at His feet. Unlike other representations of similar scenes showing Christ himself or His apostles washing feet … where they were shown kneeling in a dignified posture, here the woman was shown in a totally subservient position.” Christ in his role of the Second Adam looks benignly down on the eternally groveling penitent Eve: “In the stained glass window / enshrined in medieval forms / OFFICIAL POLICY: / woman, like a faithful dog / at her master’s feet, / is sentenced forever / to love and to obey.” Above the window, pencil drawings of women “playing the parts” of glamorous seductresses hover; however, the one at the far left shows the anguish and sorrow the rest are hiding. In subsequent scenes, the “token woman of influence,” the Virgin Mary, “a goddess without power / a virgin / eternally pure” is shown sitting demurely on a little cloud, behind her glorious son, and the Virgin and the Whore are shown side by side in golden shrines topped by symbols of Christianity, Judaism and Islam. Adam sits astride on top of the structure, savouring “the sweet taste of the apple” that is “only for him who writes the laws.”

The next scene, The Sentence, is an unusual one to find in a series about Eve, especially by a Jewish artist. Granirer relates that on a visit to Strasbourg Cathedral in France, she was “shocked to see that the craftsman who had designed the window chose to portray Mary Magdalene [sic] lying flat on her belly at His feet. Unlike other representations of similar scenes showing Christ himself or His apostles washing feet … where they were shown kneeling in a dignified posture, here the woman was shown in a totally subservient position.” Christ in his role of the Second Adam looks benignly down on the eternally groveling penitent Eve: “In the stained glass window / enshrined in medieval forms / OFFICIAL POLICY: / woman, like a faithful dog / at her master’s feet, / is sentenced forever / to love and to obey.” Above the window, pencil drawings of women “playing the parts” of glamorous seductresses hover; however, the one at the far left shows the anguish and sorrow the rest are hiding. In subsequent scenes, the “token woman of influence,” the Virgin Mary, “a goddess without power / a virgin / eternally pure” is shown sitting demurely on a little cloud, behind her glorious son, and the Virgin and the Whore are shown side by side in golden shrines topped by symbols of Christianity, Judaism and Islam. Adam sits astride on top of the structure, savouring “the sweet taste of the apple” that is “only for him who writes the laws.”

Granirer describes the year-long Trials of Eve project as a personal spiritual journey involving her recognition as a Jew that the jealous warrior God “Jehovah” had lost his appeal for her, her struggle with her own Cannibal Birds of fear and conscience, and her own quest for a vision of a humanity where the two halves of the puzzle, male and female, will interact as equal. In the questionnaire, she states that shortly after The Trials was published, she read and was excited by Elaine Pagels’s Adam, Eve and the Serpent, and that subsequently she has been an enthusiastic reader of feminist theology/thealogy, especially works by Jewish scholars. Her implicit Eve/Job typology is original, as is her reinterpretation of the “temptation” in terms of Kwakiutl mythology. Her identification of Eve with the stereotype of Mary Magdalene as the eternally grovelling penitent whore is also a piece of striking feminist theological interpretation.

From Feminist Theology with a Canadian Accent : Canadian Perspectives on Contextual Feminist Theology

Edited by Mary Ann Beavis with Elaine Guillemin and Barbara Pell

Novalis, Saint Paul University, Ottawa, 2008.

Included here with the permission of Novalis, Saint Paul University, Ottawa

For version with footnotes, click here

Testimonials for The Trials of Eve limited edition book:

The poems follow the art adroitly, they are illuminated by the visual image, they don’t compete for the same space in our attention, or our senses. One serves the other as the script does an actor. I wouldn’t change a thing. It is too beautiful a relationship to break up.

George McWhirter, poet and Head of Creative Writing

University of British Columbia

Granirer is another Eve, recreating herself in the image of a more inclusive humanity.

Lucy Lippard, art critic and writer

New York

After seeing and reading Granirer’s THE TRIALS OF EVE, we will not think of Eve, the fall from grace or the expulsion from the garden in the traditional way again.

Ann Rosenberg, artist, writer and curator

An amazing accomplishment. There is a sense that runs through all the work that you have remained true to yourself without being caught up in the trend of the moment – or of the decade. There is also a sense of the defining moment, the revelation, the satori which is deeply moving and then is mined for inspiration.

And a sense of incredible work, of devotion to your work which has run through your whole life. This work – and this show – prove what we have known all along, that you are a fabulous artist!

Sometimes it takes a show this extensive, however, to prove it so conclusively.

From the visitor’s book for Celebrating a Life’s Work

Richmond Art Gallery, Richmond BC

Ed Varney, artist, curator, writer

1998

Reviews : Selected Excerpts

Pnina’s work is the kind that you could live with for years and still discover something new.

Laura Anne Holden, Granirer’s art truly unique, The Tribune, Winnipeg, Manitoba

October 10, 1979

Here are works whose strength, power even, which we are happy to salute. At the same time, Pnina Granirer’s work is typically feminine, with its flexibility, its seductiveness and its imaginative expressivity. This exhibition deserves more than just a casual visit; it deserves to be allowed to lead the viewer towards the mystery of the artistic creation, the reflection of the original creation itself.

When Canadians distinguish themselves by originality

Works by Pnina Granirer at Galerie Artal

Le Nouvel Alsacien, Strasbourg

April 19, 1980

Granirer’s exhibition achieves a success that belies the seeming simplicity of the works. Most effective in the exhibition is the transition one sees in moving around the gallery: the child gives way to the youth, who eventually becomes the middle-aged recluse. The works carry the concept mercifully and with subtleties one does not apprehend until much later.

Jerry Szymanski, Of Women and Black Rose, Chrysalis Gallery, Western Washington University

The Bellingham Herald, Bellingham, Washington

October 5, 1984

Even though the artist has already exhibited twice before in Strasbourg and thus is not a stranger to us, she still surprised us by this new height which more than justifies the international reputation she has developed for quite a few years now. All the more so, since far from repeating herself, she treats the most original themes with great control and sobriety, suggesting the silence of the space disturbed by the rumbling of the ocean and the piercing cries of the seagulls. And also by an overwhelming sense of poetry.

Jean Christian, New Works by Pnina Granirer, Galerie Aktuaryus

Les Affiches Moniteur d’Alsace et Lorraine, Strasbourg

February 10, 1987

Over 30 years ago, when Granirer began her career as an artist, she began a process where questioning and self-reflection were important in her work. There is a definite sense of freedom and joy expressed in these works which convey moments of understanding and enlightenment, mixed with passages of questioning and confusion. …Granirer’s search for Eden is ageless and endless and will, I am sure, ensure many more years of output from this dedicated artist.

Amir Ali Alibhai, In Search for Eden

ArtFocus

Fall 1995

… the artist effectively uses the methods of deconstruction, torn fragments, stenciled texts and juxtaposition of incongruous imagery to focus attention on the process of image making itself. The resulting effect is intended to undermine our confidence in the orthodox and essentially male formulations of both women and nature’s traditionally conceived femininity. In this exhibition we sense the groping of a keen mind in its search for suitable icons in a world from which the sacred has already been excised.

Archie Graham, The Carved Stones, Smash Gallery, Vancouver, BC

North Shore News, North Vancouver, BC

November 20, 1991

Pnina Granirer’s most recent work appears neither angst-driven not a vehicle for popular political agendas. Her hard-won artistic feminism (as opposed to ‘feminist art’) is evinced through an emphatic demonstration of a woman’s passionate visual experience, sparkling internal fantasy and daring association.

Ted Lindberg, Granirer: Portrait of an Artist

1998

Granirer’s recent mixed media works are simpler, less ideological and more exuberant. In these she is mixing it up, tossing it all in the air to see which elements settle on the eye of the beholder. They are frankly celebratory.

Yvonne Owens, The Golden Devil Charm of Pnina Granirer, Richmond Art Gallery

Artichoke Magazine

Spring 1998

It is Pnina Granirer’s facility for visual language that gives us immediate access to her imagination. Originally, intellectual content, stylistic integrity, cultural and artistic influences – these qualities evolve and mature. Command of visual language appears in the early work and remains throughout and when she brings this facility to an exploration of identity or gender politic, it is immediately clear what she is working out. When she shifts the exploration beyond the personal or even cultural, into the visual experience and perception, we are reminded that “seeing” is the result of perceptual habits. And hers is based on a nurtured imagination and artistic discipline. We get a pretty good show.

John Weber, Review of Pnina Granirer: Portrait of an Artist

Books in Canada

May 1999

She’s outspoken, feminist and subversive, but her deepest loyalties are given to what remains most keenly “human” within us in the face of ideology, mythology and technology. Granirer depicts the tender vulnerability of flesh most poignantly in these new drawings and paintings, with an unidealized treatment of anatomical volumes and forms and an expressive, flowing treatment of gesture and line.

Yvonne Owens, A Look at the Local Galleries

Monday Magazine

November, 2000

I have always wondered why the most powerful drawings come from smaller, slighter built, even timid people. Granirer has an ability to connect herself with her subject matter and become a conduit of that energy for her own personal interpretation. What is unique is, she doesn’t lose sight of what information is important to put down. This is openly shared with those who wish to experience, learn and remember.

Paul Constable, Pnina Granirer – The Love Making of Art

Artistsincanada.com

March, 2003

The soft body versus the hard world: perhaps this is the human predicament. Vancouver-based artist Pnina Granirer has been exploring this dichotomy for the past six years. Her exhibit, Synchronicity, at the Zack Gallery in Vancouver’s Jewish Community Centre, evokes the complex relationships between humans and their contemporary settings. In particular, Granirer is concerned with technology’s mediation of human perception and expression. Through a range of materials, her imagery features dancers, acknowledging the inherent directness of their discipline.

With a touch of irony, Granirer incipiently worked from photos she had taken at Ballet BC and Kokoro Dance rehearsals. But the resulting works are active and responsive. Her translation of the dynamic presence of dance does not simply rest in the imagery, but in the variety of presentation of the pieces. Each of her figures, whether on canvas, mylar or paper, has a quality of energy. They leap, stretch, fall, collapse. The images’ defining lines have been erased, etched, scratched, blurred and overlapped the way a body carries the records of life’s (mis) adventures. Her marks are made with values from the most ephemeral chalk marks to light-denying black paint. Granirer is one of Canada’s veteran artists, classically trained in Israel and Europe, with over 40 years of work behind her. Her interest in the human figure is evident throughout her career, but in the past six years she has focused on it exclusively.

“The purpose of these works is to express the synchronicity of these two basic, non-verbal human activities, dance and visual art”, she says in her artist’s statement. Even the viewer’s physical movement affects how one sees the works. Their presentation includes images of dancers in Plexiglass boxes -a flat drawing in the back of the box and another on a sheet of clear mylar bulging towards the viewer. As one moves past the box, both figures shift in a simple but animated tableau. Other drawings of dancers revel on clear mylar sheets which hang suspended from the ceiling, removing them from the rigidity of walls and frames. In a solo exhibit at the Yukon Arts Centre, Granirer had installed the clear mylar drawings against the gallery walls. One was set forward across a corner giving her the idea to have many of them hung freely in the gallery space. Not only do they shift and interact with each other as the viewer moves, but ambient lighting casts an entire troupe of shadows on the walls around them. During this year’s Chutzpah! Festival in early March, graduating students from Vancouver’s Arts Umbrella dance program added a live, performative element by dancing in and around the drawings. They improvised in direct response to the images. Granirer describes this as the “interaction between the live body and the imaginary one”.

Bettina Matzkuhn, Pnina Granirer – Synchronicity

Medical Review Magazine

November 22, 2005